Portraits

John Wallace

< v

Glasgow, UK, 19th of November 2015, Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

JW: No, I never felt that I was a trumpet player or a cornet player, or anything like that.

Basically I thought I was a musician, and [the trumpet] was the vehicle for expression -

for self expression within a collective, a collective expression. I was brought up in a

Protestant Scottish background, and we are taught to subjugate the self for others. We

are taught to look at ourselves and see ourselves as others see us. We are very selfconscious

from the start, so I was very conscious about the trumpet being perceived

as a loud, brash instrument. Brass players were being looked on as being vulgar, and

brass bands were at that time beyond the pale - which means that they weren't polite,

and you couldn't talk about them in polite society. To like brass bands was of a vulgar

taste, so I was complicated by all these things so much that I almost got a phobia

about it.

The trumpet has always just been a vehicle for me, and I have been ambivalent about

the trumpet. I find the trumpet is something that you try to express universals on, and

you steal things from other instruments - like the violin, the human voice and the piano

- and try to do things like that. I never thought that the trumpet was this one big thing.

For me, I suppose it became my identifier, and it is interesting now that I have retired

from life as an administrator that I have gone back to the elemental. That I have seen all

of this early confusion and so on, and now I am going back to the trumpet as this really

wide interest - wider than just this narrow view of a war-like trumpet that is super

phallic and expresses manhood, you know.

MB: Did you hate the trumpet?

JW: I hated the trumpet at one stage when I was about 17 or 18 because I had all

these adolescent complexities. I had been obsessed with death since I was around the

age of 9. It was then that I started to have nightmares. I think it must have been

because of the stories that my parents had told me about the German bombers

coming across the house to come and bomb Clydeside. I had this airplane engine

sound, and in my dream all the bombers were coming. And then it was just black, and

that was it. That was death. I had a happy childhood, but those were the nightmares I

had when I was the age of about 9. I can remember thinking, "I don't want to be 10! I

don't want to be 10! I am 10 - I am going to be ancient! My God, I've got two figures

now. I am 9, and I am happy... I don't want to be 10!” And then, when I got to 15 and

so on, it was maybe one of the happiest periods of my life. Bnd then I got this

adolescent thing: acne - and it was all over. I developed this self loathing - this self

hate. Everything that I was good at I put behind. I took it for granted that I played the

trumpet. My teacher in school said, “You need to play a musical instrument that has

repertory. This is Dennis Brain on the horn. He was fabulous. Listen to these

recordings.” So I took up the french horn when I was about 17 or 18, and my father

was terribly against that because he had bought me my first trumpet. He brought me to

Glasgow, bought me my first trumpet, and it had Kenny Baker's signature on it. It was

for a hundred Pounds. It was a Besson international. But then my teacher got this horn

for me, so I played the horn for a bit. I got quite good on the horn, but I played in the

Carnegie Hall in Dunfermline and I played the fourth horn in the “Nutcracker Suite.”

And playing the fourth horn...I realized how difficult it was to do - to play the fourth

horn. Suddenly, I had another epiphany that if I were going to do music and was going

to be taken seriously, I was good at the trumpet. I was better at the trumpet and cornet

than on the horn. So I switched back to the trumpet and I got a place at King's College

Cambridge because I was a trumpet player and I came from a working class

background.

JW: The successor to Ruth Railton was looking for talent..and this is a thing

about these colleges that have got choir schools: they look for musical talent

absolutely everywhere. So David Willcocks saw this young boy and thought, “Oh, this

is great, we've got a trumpet player.” So I went to King's College, and John Miller did

exactly the same thing after me. It's been very mixed and complex that the trumpet is

shown through all of these doubts and confusions and this obsession with death, you

know. Obsession with dying. Death is inevitable, but when you hear the sound of the

trumpet it is so optimistic. And this fantastic thing about the trumpet that I have

realized now in my 60s is that when you hear the trumpet and it's got this soul in it from

the player, it’s as if time stands still and, suddenly, you're in control of death and

destiny. That is what the trumpet really does for me. So I think, as I return to my

childhood - life tends to be this big cycle - it is becoming pure again. We were much

more mature as young people than we were getting credit for. I can remember that

moment at age 9, when I confronted death and thought, “I am going to be 10. Time is

moving on. What am I going to do with my life? Nine years, and I have done nothing! I

am going to be 10” Then when I got to 15, I got Ruth Railton and the orchestra and

everything, and of course it was a big confusion. I couldn't think clearly. But now in my

later years, I think I am starting to think with a clarity of an 8 or 9 year old again. When

people say “mature, mature,” I am trying to become younger and simpler. That is what

the sound of the trumpet does for me, now.

Mazen Kerbaj

< v

Berlin,

5th of February 2016,

Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

MK: When you press this here, first you have quarter tones, same here

(Plays)

It changes the sound here, so when I do

(plays)

but if you (plays)

Wife: Oh my god!

MK: It's crazy, right?

Wife: Amazing!

MK: So we're going to kill him, and I keep the trumpet!

Wife, Ok, which method are we going to use this time?

MB: A sharp knife, please

MK: Yeah, this time I will do it!

MB: Use a sharp knife!

MK: (When I was in) an age to ask things, so I would ask what is this, or what is this, it's

a table, what is this sound, it was a bomb of course, so it was part of our daily routine,

the daily soundscape. So you grew up with it as just a normal thing from your

surroundings and you don't ask yourself. And then you grew up you begin to understand

it's war, people are dying, but still it's like... it's a game. The more I was getting old, the

more the souvenirs were tragic. Not only because of death, but because of course after a

certain age, I was afraid of the war. Until a certain age it was a game.

MB: do you know when that turned?

MK: Yeah, I remember one day, because until a certain age it's a game, and also you can

not be afraid, so "no, we are very tough, we are kids, so..." you don't really admit you are

afraid, or you are not afraid. Then I remember once a huge, very close bomb, I would say

now maybe I was 9 years old but I can't remember really. And I remember being very

afraid at feeling I might have died with this, it was really in my neighbourhood. Many

bombs before fall in the neighbourhood, but this one specifically was really very close and

I really felt I could die. And I was very afraid and I was very ashamed to say I'm afraid in

front of my cousins. Because It's like saying "I am a Sissy", you know,

MK: The war really invited itself in my work back then, so I couldn't... Now some of my

things, of course, I mean it's my life, so of course my life is fed by what I... but I'm as

much influenced by wars, and I'm influenced by reading Franz Kafka or seeing Tarkovsky,

or I mean by all the baggage that I put in my, my mother calls this your own reservoir. So

there is a reservoir in me that I get ideas from, and this reservoir is fed at least as much, if

not more, by all what I read, by all what I discovered, what I heard what I saw etc. more

than by my childhood of course...

MK: Of course I tried to take trumpet lessons. And after 7 courses with a jazz musician,

we had to stop. He didn't believe what I was listening to was music, so... And then I

began to discover silent improv, I don't know what to call it, but I mean, not improv like

Peter Brötzmann, but improv with textures and stuff. I began to understand, it's not the

power you need to...and I began to train by night. My wife was pregnant, I couldn't do

sound, so I would train an hour, two hours just on this (demonstration), and discover this

small sounds.

MK: When I began to put tubes on the trumpet and discover with the saxophone

mouthpiece, and discover I can make the same sound almost on the saxophone, but I

can not play, then of course the first day I discover these things that I can make vibrate

on top of the trumpet. My interest in the instrument comes back really huge. And a little

later I begin to understand how much better, how it's the ultimate instrument for me

because it's multidirectional.

MK: So I always found the trumpet very austere and very un- preparable. And then of

course it's funny when you know what I do today with it! So, it took time to understand

how preparable it is, because my idea of it is really, it's really a sound generator in the

best sense of the term. A generator in the sense that you feel it from somewhere and it

goes from somewhere else, and you can alter everything with the valves, but it's really

focused there.

MK: Also, I don'T know if there is another instrument like this. There is brass instruments

like this, but it's all this observation I made on being not trained as a musician, it'S things

I discovered just by experience. It's one of the rarest instruments, rare instrument, where

the sound is projected far from you, as a musician. So you never hear what everybody is

hearing. Never. It's really the relation like, it goes from you, you feel it passing, and then

you throw it away. Yeah, like calling, you throw it away from you. And it's quite interesting,

this is why also it's close to, like you're saying, to talking or the voice.

MK: I came to improv, just to play improv, to music. And I find it fascinating that, as a

language, it's as close as you can get to a universal language. And it's not music that is a

universal language. Because music, if a jazz player wants to play with a classical trained

musician, and with a didgeridoo player, and a drummer from Africa, they can! But each

one has to do compromise. Each one has to change what he plays to find the common

ground to play. With improv you can take 4 people from these 4 countries, with very

different background, very different human background, and then they can work together,

they can play from the first... I mean yesterday with Pauline, for instance, we never met, I

mean of course, I know a little bit her music, she knows mine, but I could not know at all

MB: What's going to happen

MK: And we can meet, and we can talk in real time, we are having really a conversation

Rajesh Mehta

< v

Cologne, Germany,

19th of November 2015,

Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

RM: It’s called the helicopter trumpet

And then, build from that, the trumpet is later,

MB: what is that?

RM: its a Vogelpfeife, a bird whistle, so this is how I play with great drummers and

repeat the rhythmic patterns between 2 sounds

MB: the moment of choosing the trumpet: What was that like? Why the trumpet?

RM: Obvious. There was never any doubt in my mind. I mean, if I was meant to play an

instrument it was this. It was just the sound. It was something. I felt my sound... My

imaginational sound, musical sound was in that instrument. I’ve had questions over…

Let’s see, I started when I was 10, so 1974. And now I’m 52, so I’ve been playing for 42

years. There have been moments where I’ve thought, “Ok, well maybe the soprano

saxophone, so if I would be doubling on that …” But I’ve never gotten closer to Indian

music before I made this slide trumpet. So my challenge has been all these other

sounds: natural sounds, and electronic sounds, and sounds and technology… and also

traditional sounds… to find it on the instrument, and then to expand it.

MB: But why the trumpet? It’s loud, it’s difficult to play, it’s obnoxious…

RM: Right. And it’s beautiful and powerful and exciting and… I think I was also

attracted to the role of the instrument. It’s very melodic - like if I heard Louis Armstrong.

It’s song-like. I think one of the things I was attracted to was that it’s song-like and I

had a lot of vocal music in my ears from my childhood. So Louis Armstrong was

probably the first, and he was a singer and a trumpet player. And so I think it had to do

with the vocal quality of that instrument. Even the South Indian temple music is vocal.

It’s actually sung. These are songs. These are devotional songs which singers sing, you

know. There’s text there. So I think it was the vocal aspect.

No, I don’t think there is an archetypal trumpet player, but there are archetypes that

work through the trumpet. Like being the “Urvater" or “Mutter”... whatever it is. But I

think music can reach deep into the psyche to, you know, allow those archetypes and

then it has… Why I love South Indian music is that is has been consistently connected

to healing. Is is about the inner healing power. It’s about the power of sound to heal. So

it’s the therapeutic or healing power of music. It’s actually used to scare evil spirits

away. That’s why it’s so strong and penetrative. And there is something about music

and healing and re-balancing forces in the world. So I think, you know, and that takes

also penetrating force. And the trumpet has that. Trumpet has the ability to penetrate…

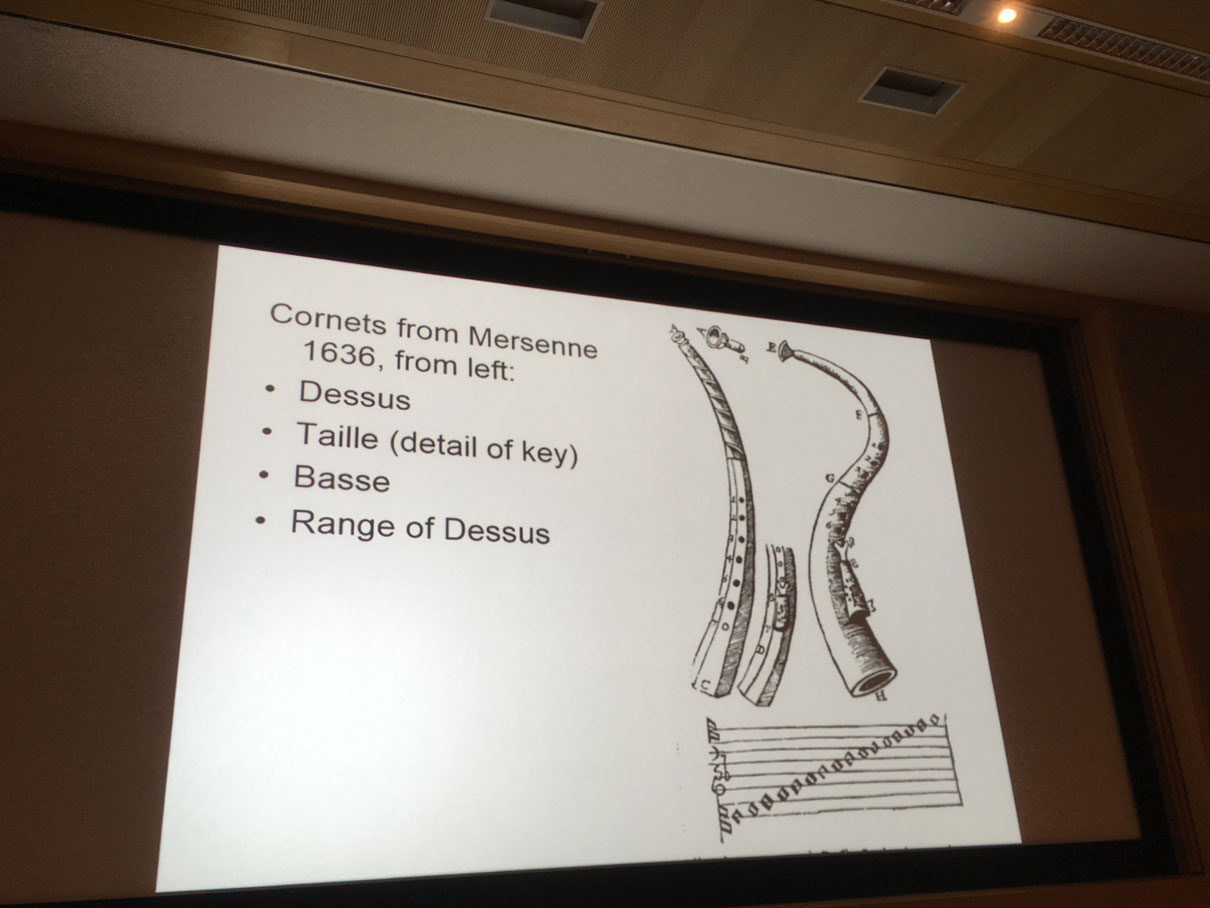

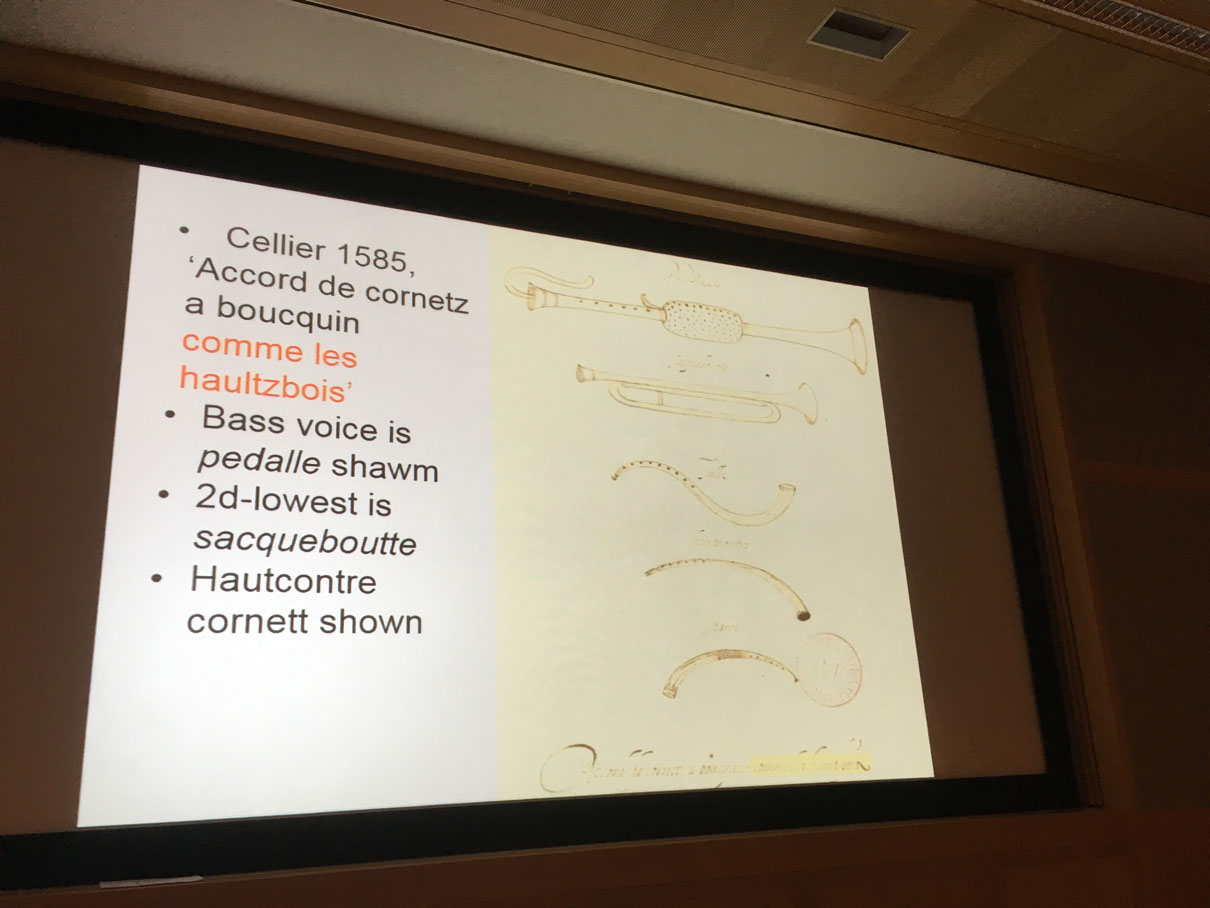

Bruce Dickey

< v

Utrecht, The Netherlands,

22d of March 2017,

Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

Marco: you represent historical music on the stage to preserve the history or do you

feel your contemporary performer? (56:28)

Bruce: Very definitely a contemporary performer, but not only. I would say it this way:

the motivating factor for me is my fascination about the way they played in 1600. The

thing I would most like to do is to go back for 10 minutes to St. Marcus and hear what

they're doing. Not because I necessarily want to copy it, probably I would find it so

strange, I think, that I wouldn't know how to process it, but I have been sort of

obsessed all my whole career seeing this whole thing as a puzzle. What did this music

sound like? What did the players think about it? How did they approach their

instruments? And there are all kinds of little pieces of this puzzle we'll never be able to

put the whole puzzle together, but pieces of the puzzle are things like historical

instruments that survive in museums or music manuscripts in museums. Organs that

are still in there or have been put back in their original condition and temperament from

which we can learn a huge amount.

Marco: But for me these are technicalities where maybe the perception of those people

of sound would have been completely different, because the environment smelled

different, sounded different, they didn't have a train passing by.

Bruce: Oh, I'm sure it did, but all we can do is, I only mentioned a few of them, other

ones are maybe more important, studying descriptions of the instrument, but even

more than that the kinds of musical contexts in which the instrument played, because

that tells you something about how loud it was played and how bright it had to have

sounded. So, if you see it has to play with a violin, it has to play with a voice, it has to

play with a historical Italian organ you get a picture of all these things together. But I

mean, for me almost as important going into a church like St. Petronio in Bologna and

going back in the organ and seeing signatures of cornetto players carved into the wood

from 1560 and just touching that and going to a museum and holding the manuscript or

the print of the Monteverdi Vespers in your hands and not just seeing it on a digitalized

photo, but feeling the paper. All those things, I mean it's all very peripheral, but you get

a feeling for the texture of what it was like. So I like to find how many of these little peep

holes can we find into the past so that we can try to feel connected to those people,

but there is no hope that we can sound like they sounded, so that can't be the goal

anymore. I mean, I don't know. Dalla Casa was one of the most famous cornetto

players. People say to me 'oooh, but I think you are the greatest cornetto player of all

time'. I think that if I went back to 1600 and play for Dalla Case he would scratch his

head and think 'what is this?' and I would probably think the same thing of him.

Bruce:

’will the lips vibrate?' They will vibrate if I'm not thinking about them vibrating. It has to

be a response to an image of sound that I have in my head and then it will speak

always. But if I start thinking about what my lips are doing then maybe not. And that is

connected to finding the air pressure and air speed immediately from the beginning of

the note and not letting your tongue block the air and then you got a burst of air and

then the flow of air settles in later. It has to be just like a singer (sings a note). So what I

find so wonderful about that program is the singer and me imitating each other and she

does that work for me. She begins a phrase and I imitate it and I have that feeling of the

sound already there and don't have to create it. The thing that you want to avoid is that

feeling of the room being silent with on vibrations, I take a breath and I have to

somehow break through that silence and create a sound. It has to be there either

because someone else is playing or singing or because you have it in your head and

then it happens.

It's air! I used to have to tell myself more technical things like walking on stage I would

say to myself 'just give relaxed slow air, then the sound will come' and you relax.

(01:23)

Marco: It's like a discipline of thoughts!

Bruce: Ja, but it's much better if that can be connected to a musical idea and not just a

physical, physiological idea

Marco: So there is also a difference in contributing to sound that is already happening

and starting

(05:57)

Bruce: Absolutely. And I have noticed in my career how much easier it is if you play a

canzona and you're the second voice to enter. It's so easy to enter as a second voice,

but if you're the one who has to break the silence it's much harder

Laura Vukobratovic

< v

Essen, University of the Arts,

7th of November 2017,

Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

n... so for me that time in Yugoslavia, so I say Yugoslavia, at that time it was called that way, it

was a kind of a whole world. That was, the possibility we had at that time, that was of course

through music, or school, or all day just playing outside, except when we had to practice, that

was always very... that always played great importance in our lives…

M you had to?

L Yes. We had a teacher who was very strict, I can say that.

M. From what age?

L. Well, I started to get really involved with trumpet when I was six. Actually, I could already buzz,

and started to play the trumpet, that's when it was really so... yes... we had the system in Yugoslavia,

that was of course better than here, through the State Music School, twice a week trumpet

lessons, we always had solfège, ear training, we had chamber music and school orchestra. So

these are all these things that we all did in parallel. From seven!

And of course this whole school orchestra, that was great, so what for a weekend, Saturday Sunday,

of course then sometimes you couldn't play with your friends, "school friends", because we

always had school orchestra, but on the other hand that was great, because we traveled a lot, so

for example I have incredible memories, to a point why I decided to continue music, yes, where

you have to decide, at fourteen or fifteen, what you want. And that's what I was always so excited

about, this being everywhere, and not just in one place, but everywhere else, and meeting a lot of

people, and doing things with a lot of people.

For three months NATO bombed us every day. For three months. Completely... As a normal person,

you can't understand that at all. I still don't understand it.

and of course we all played. So we couldn't go to the university to teach, because it was on the

other side of the Danube, and there was no bridge anymore, or you thought, if there was still a

small footbridge, you thought well, now another bomb will come and destroy that too, simply that

a person couldn't go from one side to the other, so I taught at home. You are teaching at home,

and suddenly there is a bomb alarm, and you say: what do I do now? You are teaching and the

bombs are falling? It's like something one can' t imagine at all. But we really wanted to do this, as

if it wasn't happening at all. It was best to ignore everything.

M.This is how your voice sounds now.

L. Yes! as if nothing had happened. And then when it was really completely over...those NATO

bombs....

M. Didn't it drive you crazy?

L. Unbelievable! Angry! Incredibly angry. I was angry at the whole world. I couldn't understand it. I

get incredibly emotional.

M. how can you channel that?

L. I did with it in such a way that I said: ok I'll pack my trumpet and go back to Germany, and will

just continue my way.

L: I must say I have been incredibly lucky that I have never had any negative experiences here. I

have only from many of my female colleagues, for example, …studying trumpet as a woman is

out of the question.

and I am so glad that I came to Reinhold (Friedrich), to a teacher who made no distinction between

men and women. He supports, as much as it is possible, just to give us the feeling: It is

possible, there is no reason that it is not possible. Of course, it was different when it was clear: ok

I'm coming to Germany, and I want to stay here, after the war in Yugoslavia, then it was very clear

when he said: now you are preparing for auditions. Then I looked at the landscape, and I said:

Reinhold, where do you see a woman in a large orchestra? It may seem arrogant, but I said that if

I go in the orchestra, I want to have a good job, and that is of course A orchestra, or radio orchestra,

although I always preferred to play opera more above only symphonic works.

Then he said very clearly: Then be the first!

M. And how was it then? Did you then realize: I am a woman, possibly the first solo trumpet in

Germany. Did you notice that?

L. I did notice that, not in myself, but I realized that suddenly a lot of people were talking about it:

there is a female solo trumpet player. It was funny that after that... when was it...? 2002, and now

it's 2017, and there's still no (woman) in the big orchestra, and that's what I find sad.

L. I think if a woman plays really well, really well, that that's not negative, so .... But she just has to

be so convincing that you don't have to start asking the questions about whether it would be

safer to hire a man or a woman

M. She actually has more to prove than a man.

L. So she must have such a self-confidence, but not seem arrogant, because otherwise there is

always this word Emanze, this word... this is quite unpleasant word in Germany "woman who

consciously presents herself as emancipated and who actively promotes emancipation"; the word

is here considered slang and often derogatory”

L: I have to say, we sound different, we have different kind of approach to the instrument, to playing

technique. I can't say now what is better, but definitely it is different. And I can't say now, it's

more beautiful when a woman plays, or it's more beautiful when man plays. There are so many

personal things that go into it, like the idea of sound, or musical idea, warmth in sound, intensity

in sound...

but I can often hear very often when a woman plays, or a man.

But I can't say why, How if it's a different kind of warmth in the sound... It's just something different.

I can't describe yet... I'm trying to explain that for myself too.

M. Can you relate to a common human need to blow on a tube, to blow a horn, that there is also a

general need that takes place around the earth. Can you relate to that?

L. I can totally relate to that because I find simply that every person wants to convey something.

And that's an incredibly easy way to express the emotions and everything, without just putting

yourself out there, and just shouting, or whatever.

M. So then the trumpet stands in between?

L. Yes! Instead of shouting, you can be more cultivated through the instrument. I find that for

many people that... that's something that connects us all together.

Peter Evans

< v

New York City, USA,

6th of July 2017,

Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

Marco: So what is the trumpet to you? When you put it on your lips and you play what

is it you could it be any other instrument?

Peter: I don't know anymore, I mean I fiddle around with a piano sometimes. Actually

playing with people who do live electronic processing has really changed my playing a

lot and it's helped me, not even in a scientific way but just as a musician, to

understand sound a little bit better. So that I can think of my instrument as something

that is processing something else. Of course there are limits but the idea of a limitless

interface…the fact trumpet is limited appeals to me actually.

Marco: And what would you miss most if you wouldn't have a trumpet anymore?

Peter: Well I think the issue’s not really the trumpet. I think the issue more is that for

me, playing... being able to use music as an outlet. It enables me to access whole

areas of living that I don't really have a way to do those in my daily life. If I did I might

not even play music. When I read about spiritual teachers, I've been reading a bit about

this guy Inayat Khan, the sufi musician - sufi writer - he eventually just stopped playing

because he didn't even need it anymore. All the things he got from spiritual practice,

music was just kind of a stepping stone, and he passed through music. That makes

total sense to me. I mean, that's a different path. I'm not on a path necessarily. I'm

more saying that the things that are possible in music for me unfortunately aren't

possible in daily life. Music teaches me about daily life in a way but if they were

unmasked then maybe we wouldn't even need crazy music.

Peter: I mean obviously it's me doing it, I'm playing but I'm also plugging into something that

is kind of an annihilation or passing through or continuing on a certain ethos or a way

of creating, that people before you have done. These are actually the most normal

ideas in music. So it's interesting that they've been relegated, at least in the west or

even in art music communities, it is still a strange kind or culty idea. when you hear

someone talking about this stuff it's like “woah that's crazy.” No! It's super normal.The

idea that when I am playing a solo show I'm trying to let something else do all the work

and that something else is the thing that is driving. It’s not really driving me, it's

recognizing that something exists that's not you and then learning how to channel that

through your own little weird filter. I guess that's the best way I can really put it. And the

more aware I am of whatever that force is, the stronger it gets. So the more I really

believe in that, or know that it's something that is real, the easier it is for me to let go of

other things

Peter: There is something spiritual about technical craft. I do think that to watch another

human being you're watching somebody transcend what you think is even possible for

a human being. Not just on an athletic level but it's connected to some deep kind of

music making. For me that's the best. Coltrane is a great example of that, his really

ferocious technique but put in a serv... it's not like anything he plays sounds dry or like

an exercise but he has clearly practiced a lot of that type of material so that when he's

in that whatever that state it it just goes ahead

…one technique that I've found that allows yeah like a multilayered kind of space

where there's you can even get if it's kind of all in the fuzz but you can even get the

sounds of different parallel melodies at different points in the harmonic series working

in unison kind of almost like a homophonic texture of like these different melodies

happening on top of one another and then just focusing in on one of them if you want

and then exiting that space and you back in more clear space I guess...

Marco: Cool. What's the other sound I couldn't figure out the amount of noise you can

add to your sound. White noise so that you have a pitch...

Peter: Like air?

Marco: Yeah.

Peter: It's just messing with the aperture so that a lot air is kind of wasted I don't know

how else to explain it. right now it's like locked. I'm actually dropping the bottom lip

now and the aperture is opening more than it needs to.

Marco: Can you do it over the whole register?

Peter: No, well kind of. it takes a certain amount of control.

yeah, it's possible … I guess if I had to analyze it it's the same concept which is just

I'm just playing a synthesizer 'm moving all these different elements around to create a

sonic space that's layered you know so I have options and so has options so you can

choose different pathways to listen or somebody that' playing with me can lock on a

certain information but not others you know...

Cuong Vu

< v

Seattle, USA,

11th of July 2017,

excerpts from an interview with Marco Blaauw.

Busy. Honking. Loud talking. Fast loud talking. Yeah. And then some music. Not a whole

lot of music. At home, my father had a reel to reel tape recorder that we had music on a

lot, because my mother also sang, so... Musical sounds were around when we were in the

room and they put on their music.

I remember looking at the tapes all the time like, "Oh, the sound is coming out of there..."

It's amazing.

I got the impression that things were wrong when one night we were gathered and there

was a lot of talking and I had to say goodbye to my dad for some reason. I didn't

understand. And then the next morning it was still pretty dark, it seemed like we snuck

out and went into a van and then drove for a pretty long ways. And we got to the army

base. And we were shipped out.

I don't remember it being a culture shock. I remember feeling excited and that it was an

adventure. It was really fun. And then, you know, coming from a place where your space

is cramped and maybe old and maybe dirty, small, poor... to suddenly being in America

where everything seemed new. Especially our neighbourhood that we moved in to,

everything was new. A lot of nature, as you can see. Where we were was on the east side

of the lake here.

We all lived in a big house that was nice and new. It seemed wealthy to me compared to

what we had before.

... My dad was mainly a guitarist and he played drums, but then when we left, for some

reason he took up saxophone and trumpet, but more so trumpet. But I had a picture of

him playing saxophone, so as a kid I was like, "Oh, this is my dad. He plays saxophone." I

was so excited.

So I wanted to be a saxophone player, but then when I asked my mom if I could play the

horn, I didn't say saxophone or the trumpet, I said, "the horn," because it works for both

saxophone and trumpet. I was thinking about the saxophone. There was also a picture of

him playing the trumpet that I didn't really... I saw the saxophone one. So she went out

and bought a trumpet. I opened it up like, "This was not what I wanted to play!"

MB: Oh no!

CV: But then, you know, I tried to play it and it was really hard, so it stayed in the closet

for a good two or three years. And then my dad came over and said, "You're going to play

trumpet." And at that age, the music education started in grade school, in fifth grade, so,

you know, they asked the students, "What do you want to play?" And so I had a trumpet

at home, my dad said, "You should play trumpet." So I played trumpet. But it wasn't my

choice. I wanted to play drums or guitar or saxophone. And my dad said, "If you want to

be a musician you have to play trumpet," because in Vietnam, trumpet players were the

band leaders and you can make more money. So funny, so funny.

from what I know, the trumpet is a battle cry or a warning of some sort. Like: pay

attention, something is happening! I've never thought of it as a soothing instrument in

terms of it's nature. And when people start to take on any kind of format, whether it's with

a pencil, writing words or drawing, paint, sculpture, whatever it is... it's about taking that

tool and conveying their ideas. So once you get into that territory then all of the human

experience can come through that vehicle.

CV: And then I think about sound and yeah... It's a very... the kind of sound that makes you

say, "Wow yeah, things are exciting!" But then there's this thing about the sound when I

practice long tones and I start to hear certain things about the sound that make me go,

"Woah, chill." , there are those aspects of the trumpet that, probably, some of those guys

who play the big horn have this soft, fuzzy sound that could lull a baby to sleep. Or

digeridoo... That's not alarming and it's coming out of the same buzz. In the same way

that my limitations control what I play, the instrument influences how things will occur. But

to me it seems that we are always trying to overcome our limitations anyway so we can

get into vast territories about what it was supposed to be in the first place.

Sometimes when I pick up the trumpet it's like, "Agh," and sometimes it's like, "Yeah, it's

gonna happen. It's gonna be good." And when things are going really well, it feels like

nothing is impossible. Like, “Things will be cool. Yeah, I can do this."

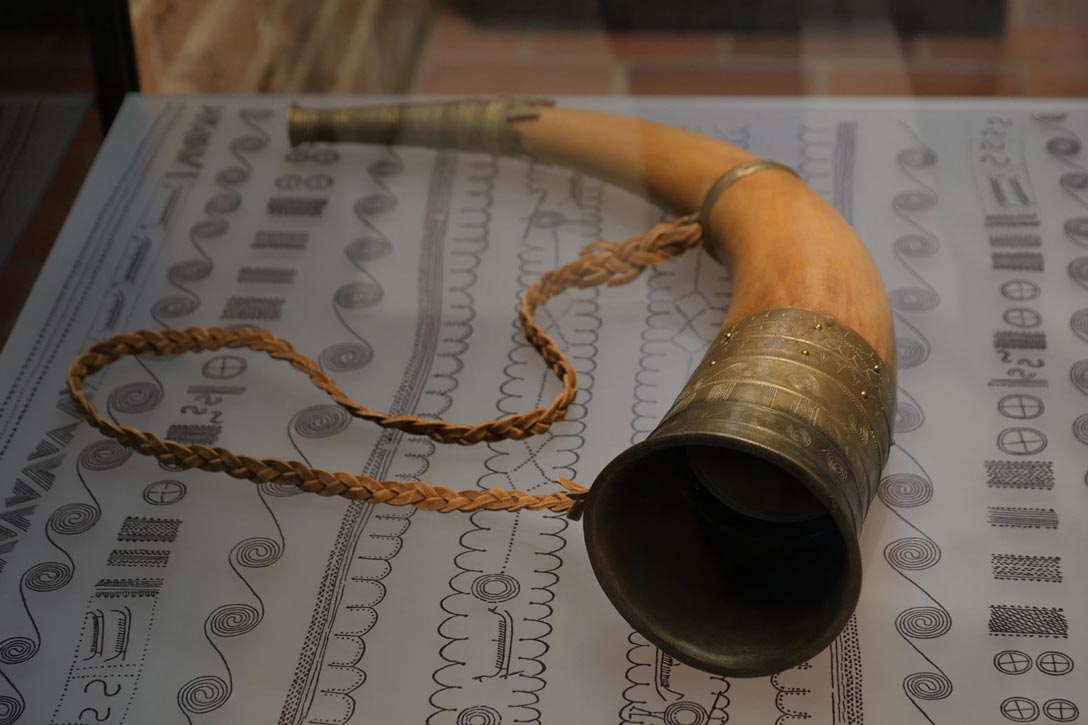

Jeremy Montagu

< v

7th of November 2017,

Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

On Rosh Hashana, New Year, you’re calling the people of Israel back to God, to

repentance, because they have ten days to think of all the things they’ve done wrong

or all the things they should’ve done and haven’t done during the year before Yom

Kippur – the day of atonement where we spend the day fasting and repenting for all our

sins and so on. So, the shofar has a very important use in that respect, and the earliest

reference that we have for the shofar, of course, is in Exodus at the giving of the Ten

Commandments. And that shofar was blown from heaven. There’s an old tradition…

That was the left horn of the ram that Abraham sacrificed instead of Isaac, and no part

of that ram was wasted. The skins covered Elijah’s loins, the intestines were the strings

of David’s harp, and so on and so forth. There’s a lot of crap of that sort. It’s great fun.

And the right horn, which is longer, is still up there and will be heard in times to come.

Which is in other words the last trump.

It’s spiritual, much of this is. It is the voice of heaven. And you feel that when you’re

blowing it.

A as a blower, I do feel that I am calling the congregation back to him or her. And if you

don’t feel that – the Talmud is really firm that if you don’t blow with intent your calls are

not valid and you’re wasting your time. And if when you’re hearing it, if you don’t hear it

with intent, again, it’s not valid. Not of use. So this is important. But the thing is that if

the people recognize the sound as the shofar they must have known the shofar already,

and we got no other reference to it at all earlier than that. But it must have been simply

a horn. I mean, it was used for battle…

When you think of Gideon attacking the Moabites where he had an army of – what was

it – 2 or 300 and they each had a shofar, each of them had a candle burning in a jar,

and they blew the shofars and they broke the jars and the flame of light and the sound

of the horns, all the Moabites just ran away.

That story. I mean, it was a war trumpet. It was used, always been used as an alarm

call in communities and so on when there’s an attack or anything like that and so on.

So it’s a horn. And it’s used for all the purposes of a horn, but it also has this ritual

context.

MB: So we don’t know which one came first: the war or the ritual?

JM: Oh, the war.

The ritual starts with the giving of the Ten Commandments after the Exodus. The ritual

was, as it were, an added extra. And the fact that the shofar sounded, not by human

agency but from heaven and all the rest of it… How was it? “The sound of the shofar

waxed louder and louder. Moses spoke and got answered with a voice.” And what God

said at that time was, “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of

Egypt,…” the first of the Ten Commandments. And so on. This is our myth, our legend.

What happened from then on, we have really no idea because in the Bible there’s no

reference to Rosh Hashana. The new year. It was the first day of the 7th month. It was a

day of blowing. It was a day of remembrance of blowing. And so on. So, the shofar

must always have been involved in whatever celebration there was of Rosh Hashana in

the book of Numbers and Leviticus where these two quotes come from.

I assume you want to hear this thing?

MB: Oh yes!

JM: Now there are the three calls that were laid down in the Talmud, about 600 –

anytime between 3 and 600 the time was written down.

MB: Can you play them again and separate them?

JM: Yeah.

MB: The first one is called?

JM: Tekiah.

MB: Tekiah.

[plays]

JM: Shevarim is a sort of wailing sound.

[plays]

JM: And Teruah, which is – means an alarm – is a sort of quavering.

[plays]

JM: And all calls begin and end with the Tekiah. Now, what the noises were that came

out, we have no idea. What I blew you is what I was taught.

JM: the whole idea of a lowland alphorn where, after all, in the mountains you want

alphorn because you’re up there with the sheep for weeks and so on - you want to

chat with the chap on the next mountain so you blow horns to and fro or you blow

down to the village and say “I’m running out of bread, bring me something” or

whatever, you know…

MB: You think it had that function?

JM: Oh yes, the alphorn certainly had that function. And certainly very much… because

you’re on your own, entertainment for yourself and also entertainment with the chap on

the next berg. And the same thing with marshes…

MB: Right, because you can’t cross over that easily.

JM: Exactly. So that’s why you get the midwinterhoorn in the Twente. And it’s why you

get the – I can’t think of the name now – the Ligawka in the Polish marshes. Again,

because you’re isolated. You’re by yourself. The chap I bought my best midwinterhoorn

from – because it’s a real traditional one – he said, “I blow. I get answers from over

there.” And so on. “And we blew to each other.”

MB: Yeah. Telephone.

JM: Well, not just a telephone. But also, just gossip. Equivalent to gossip. Today you

would use Skype.

MB: Right.

JM: But they used midwinterhoorn. It was also used during the war as a warning for

the Gestapo coming. It was also used in the Catholic Protestant religious wartime,

again to warn.

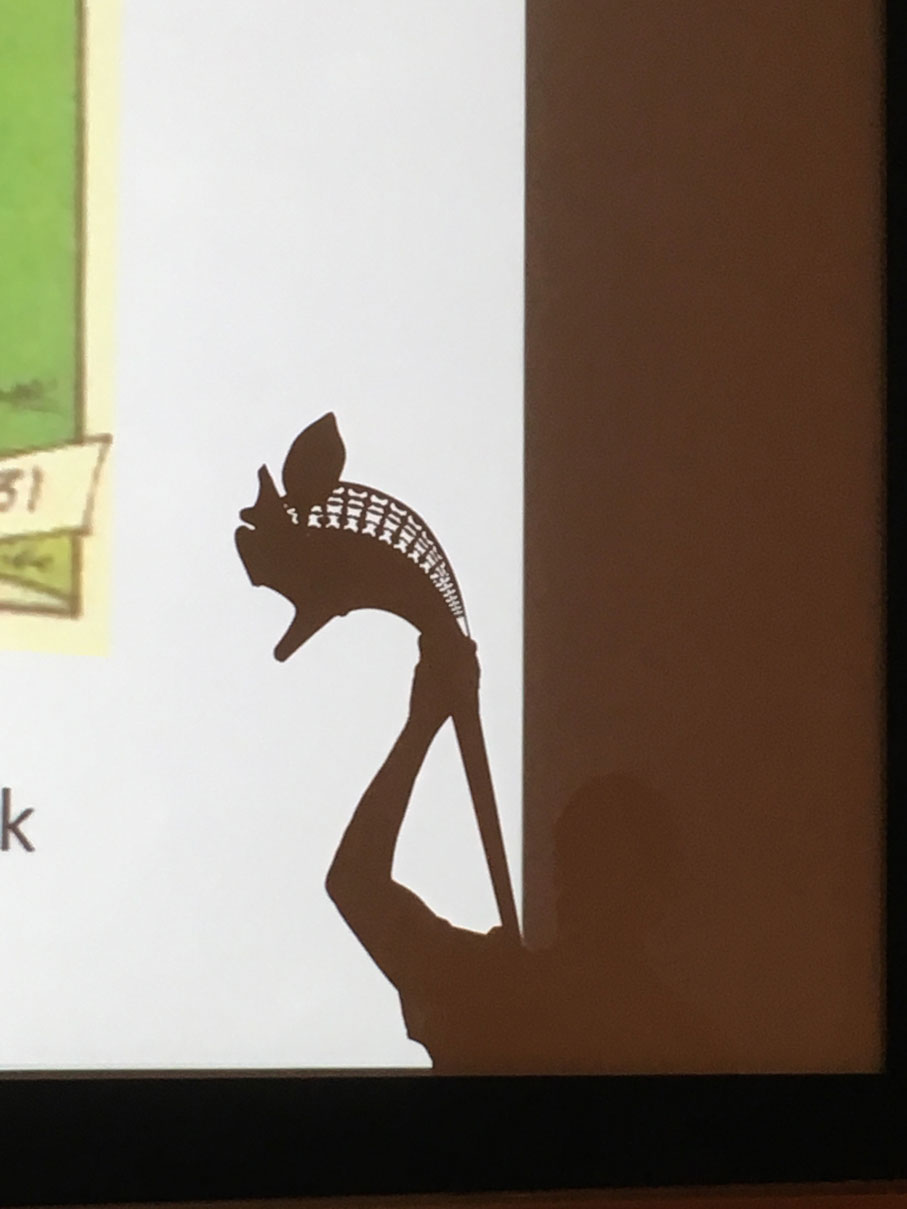

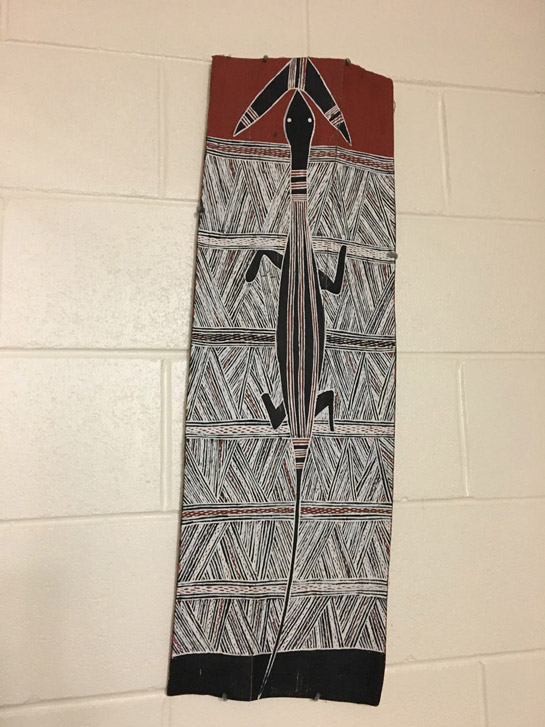

Djalu Gurruwiwi

< v

Djalu Gurruwiwi

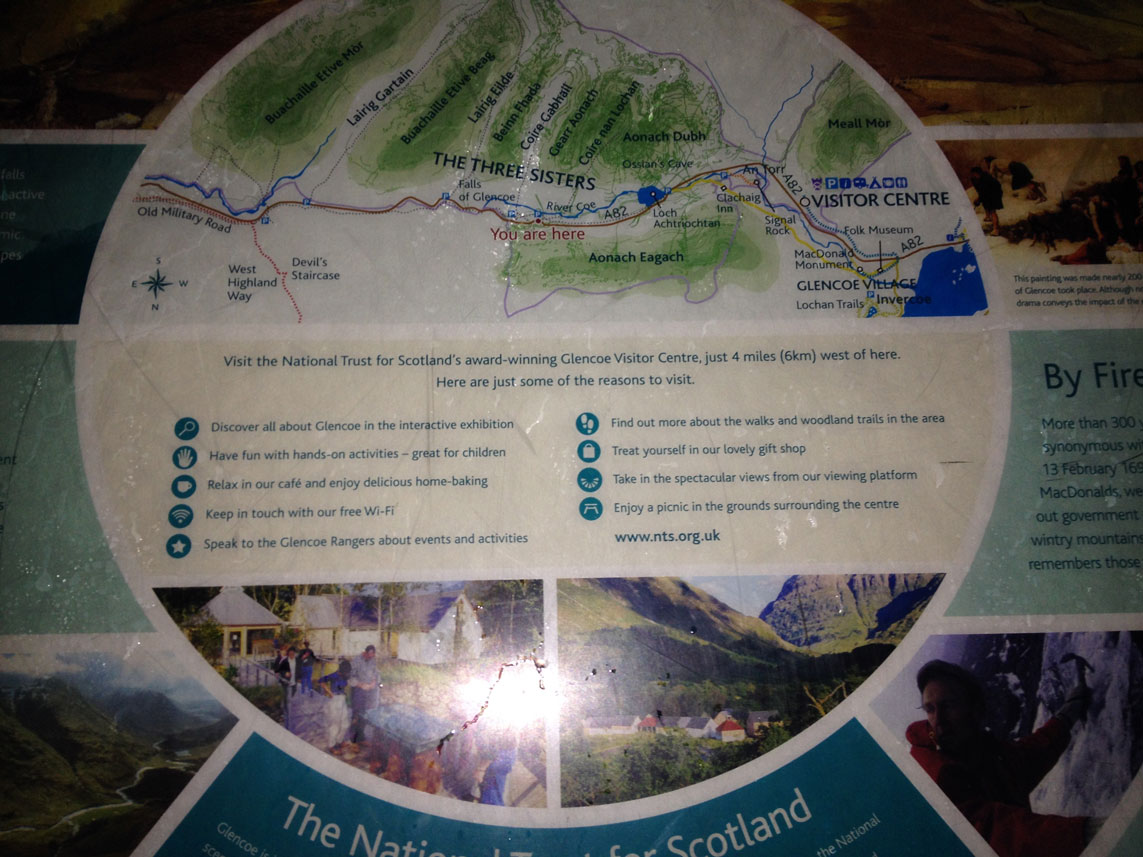

Wallaby Beach, Nhulunbuy,

Northern Territories, Australia.

D = Djalu

M = Marco

L = Larry

D: …thank you for every one of you, each that is coming from other end of the word.

Thank you for coming.

M: Since when did people start coming?

D: 2001, in 2002 I started touring around.

I tell story what kind of instrument. The tree of instrument

We have yidaki and then the tongue. That sound comes from here. Like singing. So

someone can hear you clearly…

One working. The lung turning. Went in, down. Like this. Breathe. Breathe out. Breath

in. That’s how it works. Out from here like this. This side. At the same time like … this

side. It’s moving. [sings and gestures with yidaki] See? Again in. In, out. In, out. When

you go out, the power is coming up. The heart timing. Timing. When you walk,

example. Exercise, a time – a beat. You can see. And I feel it. My stomach. I get more

power. Really like this, like this [gesturing with hands at chest].

D: I’m not talking other then... This is the yidaki quality. Qualified. Quality inside.

M: That is inside the tube.

D: Yeah.

M: You feel the pressure inside.

D: I feel it. They help me.

L: He is the master.

M: That is why he grows an old strong man.

L: Still strong.

M: Yes.

D: Yeah. I am 89.

L: 89.

M: 89.

D: Yeah. They help me. Sometime…

M: So can a balanda learn about that energy?

D: Yeah.

M: Can people of other tribes learn about that energy?

L: Yeah.

D: That’s why I tel, follow law, man, welcome. Follow law. Come. Sit with a part of this

tree. The sound is sacred. And I said sacred, because knowledge man educated part

of them. Balanda come! Can’t say no more. I can’t help. But I am this color, and blood

will be one.

M: Yeah, and blood will be one. Yes.

D: See? That’s white, that’s black. They come together.

M: Yes. Finally.

M: we can call humans around the planet with the trumpet – we can call out and

people hear from a long distance. All over the planet there’s all kinds of shapes and

forms of the trumpet, so I had a dream of connecting all the trumpets with one sound

around the planet – very big distance. Strange, huh?

D: [speaks in Yolngu]

L: Old man, he saw that already.

When you tell the story, he could see it straightaway. Yeah. He was smiling.

M: Yes. But if you were to play, you were to start the sound around the planet, what

would it sound like? What would you do?

D: That remind… with my dancing. I play yidaki. Old man – my father – I remember I

have to listen. And singing… like my brother, my eldest brother…

L: He had a brother that can sing. But my father used to play digeridoo only, no

singing.

M: No singing.

L: That’s why he… my grandfather, he listened to my grandfather and learned.

M: So that’s the sound that you would play.

L: That’s why he sings and play digeridoo.

M: Sing and play yidaki.

(2:14)

D: I had other one – one and they walk around. I would play the land. I would play a

[smacks clapsticks] walk around.

L: This is called a song line. Song line about the ancestors. In my country, I was

walking this way to the other side. This is the song line of that. [Gestures beat]

Dancing.

[playing and Djalu singing]

L: That’s the song line.

L: Song line, singing, the words, telling the story, the places…

Maite Hontelé

< v

Den Haag, The Netherlands,

4th of July 2020,

Excerpts from the interview with Marco Blaauw.

MH: the tone of the trumpet is an entire universe. That resonates in such a way, you

can compare that to the voice, but… That was what the trumpet was for me. That was

the great attraction of the trumpet - that you can say so much with one sound. And I

think that is why I find this research very interesting because I really believe that it is a

kind of primal feeling that you… Well, as a signal, but also as translating emotions,

which it really has done for me. And what I think, perhaps, or hope what has become

the essence of my trumpet playing is that tone and what is contained within it. That

with the one middle G, with the interpretation of it, the vibration, the depth of the tone,

all the connotations, the softness of it… but above all the intention, the energy, that all

comes with it. That was also one of the things I told my students - I didn't teach a lot,

but I did a number of workshops and a number of lessons - that that's actually music.

Go make music with just one note. That’s possible. It can make people cry. And if you

can do that, then you've actually made it.

MB: …how do you do it as a woman? How do I manifest myself as a woman on stage?

How can I be myself - a woman - and at the same time not be seen as a woman

playing the trumpet but simply as someone who plays trumpet well? Would you have

any sage advice for them?

MH: Yes, that you… Look, the goal has to be that you make good music together, so

that's what you're working towards. That line is the same for everyone. Or this line, this

line is the same for everyone. That is what it is all about. So that thought process, "I'm

a woman,” you actually have to look beyond that because you are all producing

musical notes which come out in the piece of music you're making together. And

maybe to… And that's almost advice to myself - but don't dwell on that moment when

you feel insecure or think, "I don't want to be seen as a woman.” You may need to let

go of that and think about making music together because that's not about man/

woman, that's about playing those notes together in a beautiful way. That would be my

first piece of advice. To look beyond that, to look at that horizon that you're creating

together.

MB: A question is, of course, triggered for the first time as soon as they become aware

that, “Oh, I'm not seen here as a trumpet player, but as a woman.”

MH: Yes, but by looking at it differently, you'll notice that you are seen less like that.

Because, for example, I've always thought, "I work in music,” and not so much "I'm a

woman in music.” I was always treated as a musician, not so much as a female

musician. That's really about how you approach it.

Mino Ryu-ho

< v

Shogoin temple, Kyoto, Japan,

August 2021,

Video commissioned by Marco Blaauw.

Many greetings to all the participants of the Global Breath Project.

My name is MINO Ryu-ho. I'm a lay practitioner living in Japan.

I have been doing my own research on conch shells, which we call Horagai, trumpets and

horns for many years.

I was baptized at Honzan Shogoin Temple and have been studying Buddhism for a long

time.

The Horagai (shell trumpet) is the most important tool for Yamabushi (ascetic) training.

It is written in the sutras that the Buddha played Horagai to gather all living things when

he would begin to preach.

In our temple’s training method, there are eight kinds of "Fu" for Horagai.

"Fu" means unique musical notations in buddhism.

What the FU represents is something like a radio jingle. This may be similar to the role of

a military bugle.

Every morning, after waking up, I change into special white clothes for Yamabushi and

gather some implements for prayer.

I play Horagai at exactly 7:00 a.m. After, I pray on the rooftop of my building which I

imagine to be the top of a mountain.

Sometimes, I train in the mountains for one week or more.

Dear Marco Blaauw, two years ago we had a very wonderful experience with Christine

Chapman. We discussed and played Horagai (shell trumpets), trumpets and horns. It was

just one day, but we had a great and meaningful time.

It was such an exciting experience for me because this research is my life's work.

I will play the Horagai for your happiness.

The piece's name is Shugo no Fu in Japanese. It means Assembly Song and it calls

for everyone to come together.

Thank you.

Gabriele Cassone

Taylor Ho-Bynum

Wadada Leo Smith

Peter Holmes